Q: Investors often rely on financial research when developing strategies. Your recent findings suggest they should be wary. What did you find?

Campbell Harvey: My paper is about how we conduct research as both academics and practitioners. I was inspired by a paper published in the biomedical field that argued that most scientific tests that are published in medicine are false. I then gathered information on 315 tests that were conducted in finance. After I corrected the test statistics, I found that about half the tests were false. That is, someone was claiming a discovery when there was no real discovery.

Q: What do you mean “correcting the tests”?

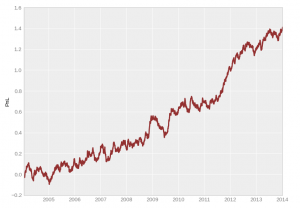

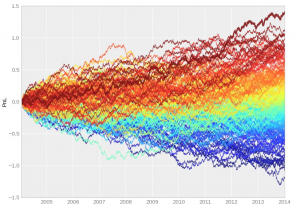

Campbell Harvey: The intuition is really simple. Suppose you are trying to predict something like the returns on a portfolio of stocks. Suppose you try 200 different variables. Just by pure chance, about 10 of these variables will be declared “significant” – yet they aren’t. In my paper, I show this by randomly generating 200 variables. The simulated data is just noise, yet a number of the variables predict the portfolio of stock returns. Again, this is what you expect by chance. The contribution of my paper is to show how to correct the tests. The picture above looks like an attractive and profitable investment. The picture below shows 200 random strategies (i.e. the data are made up). The profitable investment is just the best random strategy (denoted in dark red). Hence, it is not an attractive investment — its profitability is purely by chance!

Q: So you provide a new set of research guidelines?

Campbell Harvey: Exactly. Indeed, we go back in time and detail the false research findings. We then extrapolate our model out to 2032 to give researchers guidelines for the next 18 years.

Q: What are the practical implications of your research?

Campbell Harvey: The implications are provocative. Our data mainly focuses on academic research. However, our paper applies to any financial product that is sold to investors. A financial product is, for example, an investment fund that purports to beat some benchmark such as the S&P 500. Often a new product is proposed and there are claims that it outperformed when it is run on historical data (this is commonly called “backtesting” in the industry). The claim of outperformance is challenged in our paper. You can imagine researchers on Wall Street trying hundreds if not thousands of variables. When you try so many variables, you are bound to find something that looks good. But is it really good – or just luck?

Q: What do you hope people take away from your research?

Campbell Harvey: Investors need to realize that about half of the products they are sold are false – that is, there is expected to be no outperformance in the future; they were just lucky in their analysis of historical data.

Q: What reactions have Wall Street businesses had so far to your findings?

Campbell Harvey: A number of these firms have struggled with this problem. They knew it existed (some of their products “work” just by chance). It is in their own best interest to deliver on promises to their clients. Hence, my work has been embraced by the financial community rather than spurned.

Professor Harvey’s research papers, “Evaluating Trading Strategies“, “…and the Cross-Section of Expected Returns” and “Backtesting” are available at SSRN for free download.